Beautifully Dead - Chapter 03

An Immortal Affections serialized novel

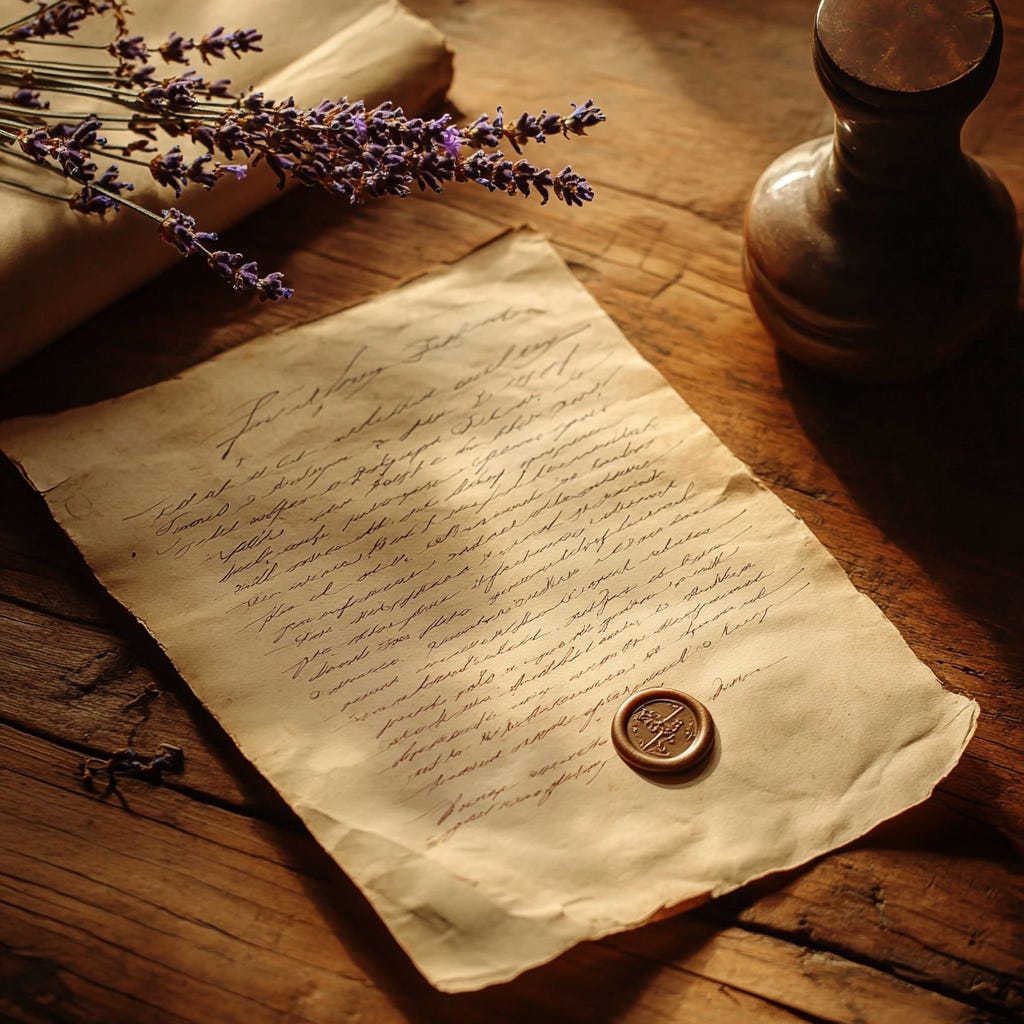

Scant hours later Amelia was laying Thomas's letter on the desk beside her laptop, the ancient paper incongruous against modern technology. The late evening shadows stretched across the hotel room, and she sipped lukewarm tea as she turned to the second bundle of letters she'd brought from the house. These were tied with a faded pink ribbon, clearly handled often over the decades, the edges softened with wear.

The return address confirmed what she'd suspected – these were Eleanor's replies. The first envelope, postmarked Richmond, Virginia, April 22, 1861, felt almost warm in her hands, as though retaining some echo of the emotions that had guided its creation over a century and a half ago.

Amelia hesitated before opening it. The letter she'd found from Thomas had been safely tucked away in the desk, perhaps never delivered. This letter, however, had completed its journey north, carrying whatever comfort and connection it could provide during those first uncertain days of war.

"Professional curiosity," she murmured to herself, carefully breaking the brittle wax seal that had somehow remained intact all these years. The handwriting that greeted her was elegant and precise, the penmanship of a woman educated to present herself perfectly on paper as well as in person:

…..

Richmond, Virginia

April 22, 1861

My dearest Thomas,

Your letter of April 17th arrived yesterday, and I confess I have read it thrice already, drawing comfort from your words during these increasingly troubled times. That you should think of me as "a pure beam of light" amid such darkness brings tears to my eyes, though I fear I little deserve such poetic elevation.

Richmond has transformed since I last wrote. The streets pulse with a terrible energy, like the gathering storm before a hurricane strikes. Never have I witnessed such contradiction—joy and fear occupying the same faces, sometimes within the same breath. The gentlemen of my father's acquaintance speak of "Southern liberation" with voices resonant with pride, while their wives count linens and discuss how silver might be hidden should Northern troops advance.

I write as the city still celebrates news that Fort Sumter has fallen. The papers claim victory; the church bells ring in celebration. Yet I find no cause for jubilation in Americans firing upon Americans. When Reverend Halloway offered prayers for "our glorious Confederate victory," I kept my head bowed but my lips still. I cannot reconcile the notion that the same Providence who guides us all would choose sides in a conflict between brothers.

Your observation regarding our Methodist Church's division as a harbinger of national fracture struck me deeply. Indeed, if brothers and sisters in Christ cannot remain united, what hope for a nation? I find painful irony that the same church leaders who preach of Christ's boundless love now encourage hatred of our Northern brethren.

Father observes my reticence with growing concern. Yesterday, he presented me with a secession cockade of red and blue ribbon, crafted by the Ladies' Aid Society. He watched with such expectation as I fixed it to my shawl that I had not the heart to remove it, though it weighs upon my shoulder like stone rather than silk. To my private shame, I removed it only upon returning to my chamber. One might wonder if such small rebellions constitute disloyalty. I wonder the same.

The revelation that you shall serve as chaplain both concerns and comforts me. The battlefield is perilous, yet I know no heart better equipped to bring solace to the suffering. I shall continue to pray that the hand that shields Daniel might likewise shield you, my own beloved lion among men.

You inquired after the peculiar cases at the hospital. There remains little to report, and what observations I have made must remain circumspect. Dr. Merriweather has transferred the patients to a private ward, and only he and two orderlies are now permitted entry. When I pressed him regarding their condition, he spoke of "contagion concerns" yet appeared untroubled by such prospects himself. Father, when consulted, advised me to respect the good doctor's judgment. I have recorded my limited observations in my private journal, though they amount to little of substance.

You will perhaps find it noteworthy that I have offered my services to the Confederate hospital now being prepared in the former tobacco warehouse on Cary Street. Despite Father's initial objections, Dr. Merriweather's intervention secured his reluctant blessing. The doctor suggested that my "steady hands and observant nature" would prove valuable as the conflict progresses. I commence my duties on Thursday next.

Regarding our continued correspondence, we must exercise increased caution. When mentioning Wesley's sermon on "Catholic Spirit" (which I referenced in my previous letter), perhaps I failed to highlight the particular passage in the fourth paragraph, where he speaks of hearts united despite minds divided. Might I suggest that in future communications, we employ the practice of noting particular hymn numbers from our shared Methodist tradition? The sentiment of hymn 319, verse 2, for instance, expresses my feelings with particular clarity. Similarly, the wisdom found in Ecclesiastes 4:12 offers comfort when I contemplate the bonds between us.

I was deeply moved by your reference to Psalm 31:20. Indeed, let us make a secret pavilion in our hearts where our connection may dwell protected from the "strife of tongues." The Ladies' Aid Society grows increasingly vigilant in their surveillance of those with Northern connections. Mrs. Pettigrew, whom you may recall from your visit to our church, inquired most pointedly yesterday whether I maintained "inappropriate correspondences." I assured her that my letters contained nothing unbecoming a Christian woman, which is true, though perhaps not in the sense she intended.

I have developed the practice of greeting each dawn with prayer at my east-facing window. Even as Richmond prepares for war, these moments remain saturated with peace. The light arrives first as a suggestion along the horizon, gradually revealing the garden below and the distant curves of the James River. In these quiet moments before the household stirs, I imagine you facing eastward in your own morning devotions, the same light touching both our faces. Despite the miles and the conflict that divides us, we share the same sun, the same God, the same devotion to truths that transcend regional loyalty.

Yesterday at first light, a pair of mourning doves nested in the oak outside my window—a bitter symbolism, perhaps, yet I choose to view their gentle presence as a sign of hope. Their soft cooing reminds me that even as men prepare for battle, nature continues its patient rhythms of life and renewal. I find myself contemplating how these small creatures navigate the world without concern for Mason and Dixon's line or political differences. They recognize no borders save those necessary for the protection of their young.

The pages of the book you gifted me before your departure (the collected sermons bound in blue leather) have provided particular comfort. I have taken to reading passage 35 on page 217 each evening. The wisdom contained therein regarding divine purposes operating beyond human understanding offers a framework for acceptance that I struggle to achieve through my own reasoning alone.

Should postal routes between us become compromised, know that my devotions will continue, unaltered by circumstance. In the words of hymn 418, final verse, my sentiment remains constant. Perhaps even more perfectly expressed in Romans 8:38-39, which I commend to your consideration.

I find deep comfort in your reminder from James 1:2-4 that trials produce patience and ultimately completion. We must hold fast to this promise as the walls rise between our regions. The newspapers report that Virginia's formal secession is nearly certain within days, which will surely bring greater challenges to our communication.

The hour grows late, and I must conclude this letter if it is to join tomorrow's outgoing post. My prayers follow you as you prepare for your new duties among the soldiers. May God's grace encompass you wholly, and may you feel the constancy of my thoughts across the miles.

With steadfast affection and enduring faith,

Eleanor

P.S. I enclosed another sprig of lavender from the garden. A memory to keep close and trust in, despite separation and conflict

…..

Amelia set the letter down gently, aware that her fingers had tightened around the delicate paper during her reading. She carefully examined the envelope again, but whatever lavender sprig Eleanor had enclosed was long gone, as had its fragrance— the flower perhaps still preserved in some other container, or simply lost to time.

The morning light now spilled through the hotel window blinds, casting stripes across the weathered paper. She hadn't realized how much time she'd spent immersed in the past.

Reaching for her laptop, she began typing notes, cataloging the historical details and potential research avenues in her personal shorthand

:

April 22, 1861 - Fort Sumter celebrated in Richmond, Virginia not yet formally seceded Confederate hospital established in tobacco warehouse on Cary Street Dr. Merriweather - quarantined patients, restricted access Methodist hymn numbers as potential code - find 1860s Methodist hymnal Verify: Ecclesiastes 4:12, Romans 8:38-39, hymn 319 v.2, hymn 418 final verse Dawn prayer ritual - potential meeting time in future? Psalm 31:20 - Thomas referenced this in his letter - creating "secret pavilion"

Her fingers paused over the keyboard as she considered the coded language. The Biblical references would be easy enough to check, but the hymn numbers would require access to the specific hymnal used by Methodists during that period. These were deliberately chosen communications, hidden in plain sight within religious references that would seem natural in a letter from one Methodist to another.

She glanced again at the letter, focusing on Eleanor's description of dawn prayers. There was something almost sensual in the way she described the light, the sounds of mourning doves, the connection she felt to Thomas across the distance. Beneath the proper language and careful construction lay passion barely contained by social constraints.

Amelia looked back at her notes, adding another line:

Eleanor already showing scientific observation tendencies - medical interest, documenting patients

Then, despite her academic detachment, she found herself typing:

Their love seems to transcend not just political division but time itself

She stared at that last line, then quickly deleted it, replacing it with:

Subject displays unusual emotional resilience and intelligence given historical context

More professional. More detached. She couldn't allow herself to be drawn too deeply into their story. This was research, not romance.

Yet as she carefully placed Eleanor's letter into an archival sleeve, she found herself wondering about the woman who had written it—her courage in questioning her community's celebration of war, her scientific curiosity regarding the mysterious patients, her disciplined attempt to create connection through shared spiritual practices.

And beneath it all, the unanswered question that had brought Amelia to Virginia in the first place: How had a Boston minister and a Richmond belle maintained not just correspondence but apparently a deep bond across enemy lines during America's bloodiest conflict?

The answer, she suspected, lay in the remaining letters, waiting to be discovered.

Loved that letter. It definitely felt of the time. I'm finding this all very intriguing