Beautifully Dead - Chapter 18

An Immortal Affections serialized novel

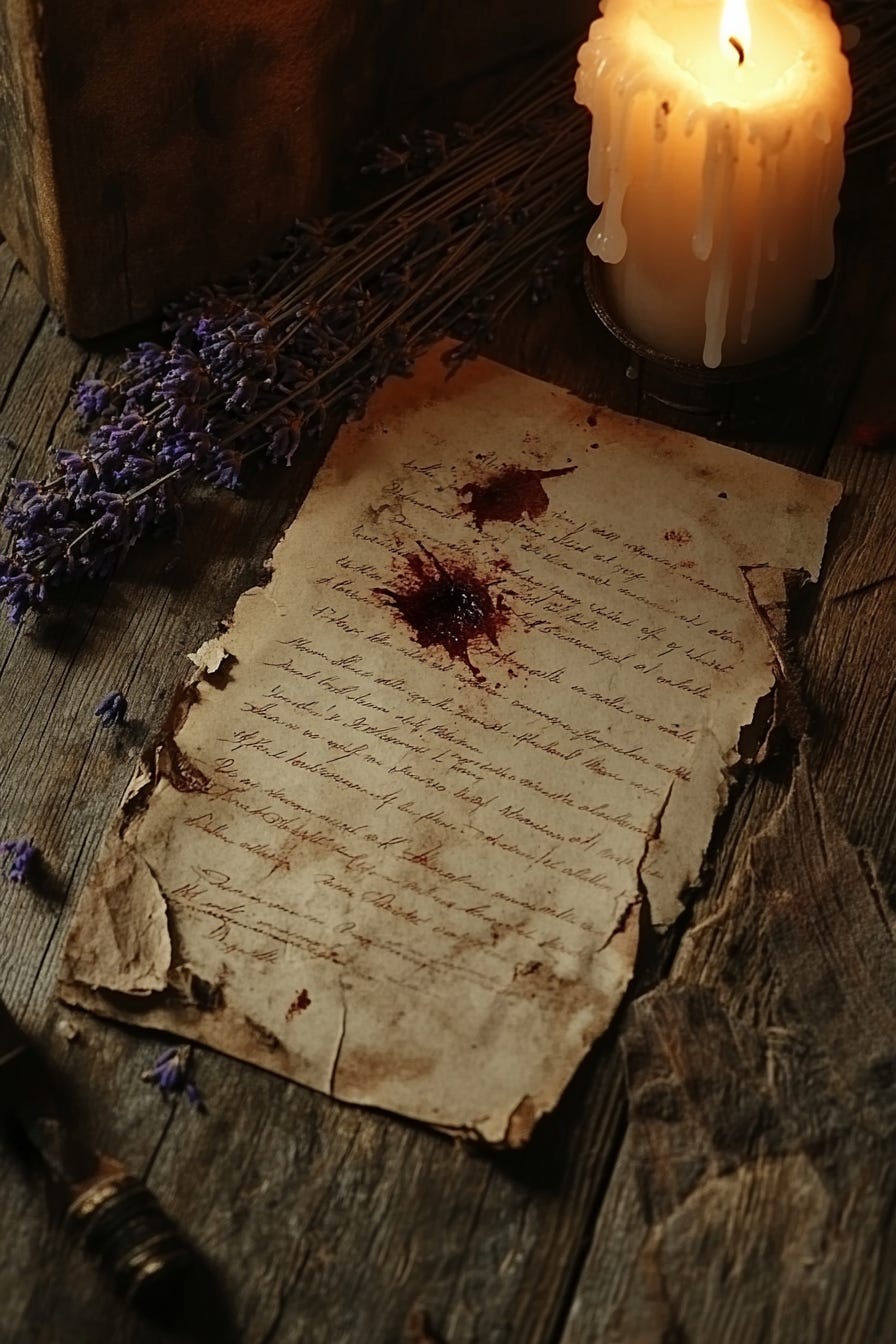

Letter from Thomas to Eleanor

Near Hall's Hill, Virginia

December 12, 1861

My dearest Eleanor,

I pray this letter finds you in good health and spirits, though I confess my own are somewhat diminished as winter settles upon us. Our regiment has moved into winter quarters, with sturdy log cabins replacing our canvas tents.

The men have shown remarkable ingenuity in constructing these humble abodes, fashioning chimneys from mud and stone that draw smoke with varying degrees of success. I have been assigned a small corner in the officers' cabin, where I maintain my modest altar and writing desk, the latter being where I now pen these words to you by lamplight.

The Lord has blessed us with relative quiet these past weeks. After the terrible events at Bull Run and the subsequent months of dealing with the wounded, this stillness feels almost unnatural. To compound it, my reassignment to the 22nd Regiment of Massachusetts has left me with men who spend most of their days drilling, chopping wood, and engaged in the thousand small tasks that comprise a soldier's winter routine. I conduct services twice on Sundays and offer prayer meetings each evening, which are increasingly well-attended as the cold drives men to seek both physical and spiritual warmth.

I find myself with more freedom to move about than during the active campaign season. The stillness of our military situation has afforded me the opportunity to visit the wounded at various hospitals in the vicinity to offer the much needed Word of God. The conditions I have witnessed, my dear Eleanor, weigh heavily upon my heart. At St. Elizabeths, where many of our most grievously wounded have been taken, men lie upon bare mattresses with insufficient blankets, their bandages changed too infrequently for proper healing. The Alexandria facilities fare somewhat better in supplies but worse in overcrowding, with barely enough space between cots for physicians to pass.

It was at the Georgetown hospital where I witnessed scenes that shall forever haunt my dreams. Men with limbs freshly amputated crying out for morphine that does not exist in sufficient quantity. Young boys barely old enough to enlist calling for mothers who cannot hear them. The stench of putrefaction and unwashed bodies mingles with carbolic acid in a miasma that clings to one's clothing for days afterward.

In these places of suffering, I offer what spiritual comfort I can. I write letters for those whose hands can no longer hold a pen, read Scripture to blind boys whose eyes were taken in battle, and administer last rites to those whom the Almighty calls home. Often, I simply sit and hold the hand of a dying boy, so that he might feel human touch as his soul departs. This work taxes the spirit in ways I cannot adequately describe, yet I know it to be the Lord's purpose for me in this terrible conflict.

There is something most troubling that I have observed in my hospital visits, particularly when tending to Confederate prisoners. Among them are cases with symptoms that strike me as eerily familiar—fevers that burn yet leave the skin cool to touch, periods of delirium followed by startling lucidity, and a peculiar aversion to light that requires their quarters be kept in near-darkness. These manifestations call to mind my father's prolonged illness, which you tended so diligently during our courtship days. It seems as though I cannot escape the constant reminders of how my family might be suffering. Has my father's condition shown any improvement? The knowledge that you continue to tend him brings me comfort amid my own physical tribulations.

I have written repeatedly to Charles but receive no reply. My heart grows increasingly troubled for my brother's welfare with each hospital visit. Has he written to Sarah yet? Does he fare well? Although he was not injured in Bull Run, the thought that he might lie wounded or worse in some subsequent engagement, while I remain ignorant of his fate, torments me beyond expression. Should you have any intelligence of him through your connections, I implore you to share what you know, regardless of how difficult the tidings might be. Uncertainty proves a crueler master than even the hardest truth.

I confess, my beloved, that my own health is not what it once was. The wound to my face from Bull Run has healed in flesh if not in spirit, leaving me with scars both visible and hidden. I find it difficult to eat, as my jaw pains me considerably when chewing anything firmer than porridge. Drinking, too, has become a trial, and I subsist mainly on thin soups and tea. These physical limitations, combined with the spiritual weight of all I have witnessed, cast a pall over my thoughts that I struggle daily to dispel through prayer and Scripture.

The memories of battle intrude upon my sleep, and I often wake in cold terror, the sounds of artillery and screaming men ringing in my ears though all is quiet in our camp. My fellow officers speak of similar afflictions—it seems this war marks the soul as surely as it does the flesh.

My faith in our military leadership wanes with each hospital visit. The generals seem to view these suffering boys as mere counters on a map rather than sons of God with immortal souls. I have heard officers speak of "acceptable losses" as though discussing the cost of lumber rather than human lives. Such callousness chills me more deeply than the December wind.

I must share with you something most peculiar that occurred during my visit to St. Elizabeths last week. While administering to a young private from Massachusetts who had succumbed to gangrene, I glimpsed a figure I recognized—Sergeant Michael Sullivan, a soldier I had prayed with just days before his reported death. Yet there he stood, observing me from the doorway with an expression I cannot describe as anything but knowing. When I approached, he vanished into the corridor, and none of the orderlies recalled seeing such a man. I tell myself it was merely exhaustion playing tricks upon my mind.

Perhaps my mind grows fevered from overwork and grief. Still, I find myself questioning whether these visions might represent divine revelation or merely the product of a mind overwhelmed by the relentless parade of suffering it witnesses.

The hour grows late, and the lamp burns low. I shall close now with the assurance of my continued devotion to you across the miles and battle lines that separate us. When this conflict resolves itself, as surely it must according to God's plan, I pray we might build a life wherein neither of us need witness such suffering again.

Until then, I remain steadfastly yours in Christ,

Thomas

P.S. I carry your letters close to my heart—literally so, as it rests within my uniform pocket alongside my small Testament. The paper has worn thin from my frequent readings, yet your words provide comfort equal to the Psalms during these dark December nights—a reminder that even in winter, spring's renewal awaits.

Thomas' Diary Entry

December 16, 1861 Near Hall's Hill, Virginia

I find myself unable to sleep yet again, though my body cries out for rest. The pain in my face has grown unbearable these past nights, far beyond what I dared confess to Eleanor in my letter. Each heartbeat sends waves of agony through the scarred tissue, as if the fragments of shell still burrow deeper with every pulse. The Regimental surgeon assures me the wounds heal well, but I wonder if some corruption lurks beneath the surface, for surely healing should not feel like continuous burning.

My thoughts scatter like leaves in a tempest whenever the pain reaches its greatest intensity. This morning during prayers, I lost the thread of my own sermon thrice, standing mute before my congregation as words evaporated from my mind. The men attribute such lapses to fatigue or perhaps the lingering effects of my wounds, but I fear something more fundamental fractures within me. When attempting to record the day's events, I often find myself staring at blank pages, quill suspended, having forgotten what I meant to preserve.

The laudanum offers brief respite, though I dare not take it, save in the darkest night when no souls would have need of my ministry. The medicine dulls the agony but leaves my thoughts clouded and my spirit untethered. I have begun to ration the drops, for I find myself craving the oblivion they bring with frightening eagerness. Is this how men become slaves to the bottle? Small surrenders to escape suffering, until surrender becomes habit?

I confess here what I would never speak aloud—there are moments when I contemplate whether continuing this life between consciousness and oblivion serves any purpose. The pain never ceases entirely; it merely ebbs like a tide before crashing anew against the shores of my endurance. In such dark hours, I understand why some wounded men choose to step into eternity rather than endure another dawn of suffering. God forgive me for these thoughts.

When I see this, I find myself questioning why the Lord permits such suffering to continue. If He is all-powerful and all-loving as Scripture teaches, why must these young men endure such torment? Why must brother fight against brother? I still believe, yet the foundations of my faith tremble beneath the weight of what I witness daily. When I kneel to pray, the words sometimes catch in my throat, as if the connection to heaven I once felt so clearly has become obscured by smoke and blood. I still serve, I still believe, but oh, how I struggle to reconcile the loving God of my seminary days with the apparent silence that greets the cries of the dying.

Yesterday Confederate scouts were observed near our northern perimeter, triggering a skirmish that left several wounded and dead upon the field. I rode out with the medical corps to offer final comforts to those beyond earthly salvation. Among the fallen was a Confederate lieutenant, gravely wounded by rifle fire, his breath coming in shallow gasps that foretold his imminent departure from this world. His position lay in a small depression, partially hidden from view—a place the Confederate retrieval parties would surely search once our forces withdrew.

When I knelt beside him to offer comfort, he clutched my sleeve with surprising strength and begged me to pray for his mother in Richmond. Something in his fading eyes reminded me so powerfully of Charles that I was overcome with a sudden, desperate idea. The letter to Eleanor—the one I had written four days prior but had no means to send across enemy lines—might reach Richmond through this dying man.

I glanced around to ensure no one observed my actions. The medical corps was occupied with the wounded who might be saved, paying little heed to a chaplain performing last rites. With trembling hands, I slipped the sealed letter into the inner pocket of the lieutenant's uniform coat, whispering both a prayer for his soul and a desperate hope that when his comrades recovered his body, they might discover and deliver my missive.

The lieutenant's eyes widened slightly, perhaps in understanding or merely in pain, before closing forever. I blessed his body and moved to offer ministry elsewhere, my transgression burning in my chest alongside the familiar pain.

News arrived this afternoon that Confederate soldiers had indeed ventured onto the field during the night to retrieve their dead. I dare not hope too fervently, yet I cannot help but imagine my letter making its journey toward Richmond—perhaps carried by some honorable Confederate officer who, despite our divisions, recognizes the sacred nature of a soldier's last request. Perhaps even now it travels southward, passed from hand to hand, eventually to find its way to Eleanor's doorstep through some act of Christian charity. The thought almost brings more comfort than the laudanum.

Tonight I feel I can scarcely order my thoughts enough to record these events. The pain builds behind my eyes until the world swims before me, letters blurring on the page as I write. My hand trembles so that my script is barely legible, yet I persist in this record, for I fear my mind fractures further with each passing day. If I should succumb to this affliction of body or spirit, let some record remain of the torment that preceded my fall.

I must end this entry, for the pain becomes unbearable again, and coherent thought slips from my grasp like water through desperate fingers.

May God grant me strength to face tomorrow's light.

…

© 2025 E.M. di V. - writing as Morgan A. Drake & Joe Gillis. All rights reserved.